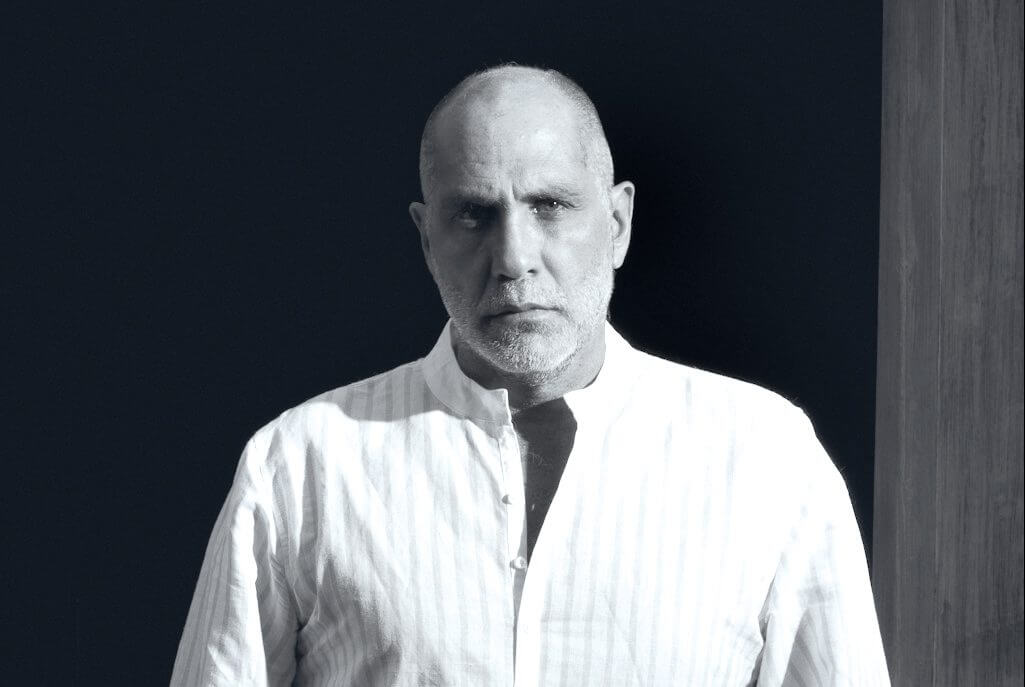

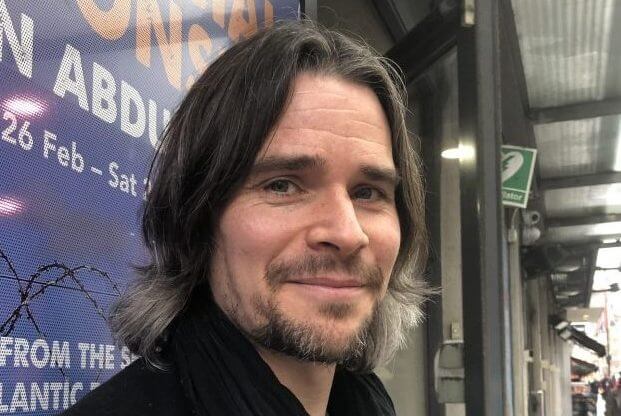

A Close-Up With Hans Matheson

I needed not one, but two straight whiskeys before this interview.

For twenty years, I’d been transfixed by the work of Hans Matheson, a Scottish actor/musician whose film credits include Tube Tales, Les Misérables (1997), Bodywork, I Am Dina, Doctor Zhivago (2002), Sherlock Holmes (2009), Clash of the Titans and the lauded television series, The Tudors. While waiting in the Soho Theatre Bar in London, the bartender doubled as my confessor. I was about to meet someone I had admired from a distance. Despite my belief that I solidly knew his repertoire, while fruitlessly trying to maintain a hard mask of professionalism, I found myself quite unprepared.

Hans Matheson was born in Stornoway, Scotland in 1975. His father, Ado Matheson, is a well-regarded Gaelic folk musician whose grandfather was crowned the Celtic Bard in the late 50s. Growing up surrounded by artistic passions and experimentations would prove rewarding for the young Matheson. His breakout film role in 1997, adapted from the stage play Mojo by Jez Butterworth, would open the proverbial floodgates; a lot of attention in a very short period of time. Yet, the cascade of film work across three decades never eroded Matheson’s creative core: film and music have lived side by side throughout his career, and he is now keen to dig deeper into the latter.

I walked into our interview eager to sate my curiosity about his life as an actor. What I walked away with was something different, some unexpected and heartening. A tireless artist consistently seeking out new avenues for expression and new audiences to interact with. Matheson is a curious, modest man with a steady, calm energy: like a soothing, bass-tone heartbeat over the shrill sounds of the world outside. His pace quickens when he talks about music. His 2019 solo album Sail the Sea, features the single “The Sun Is All Around You”, which brims with airy, pastoral tones drenched in a vulnerable, sincere warmth. He collaborated with his father on The Healing Waves, also released in 2019, an essential collection of windswept Celtic melodies.

FRONTRUNNER is privileged to share this one-on-one with Matheson, as he speaks fluidly about his life in the film industry, his new explorations into music-making, and his emphasis on mutual support and collaboration for young artists about to enter the fray.

March 2020

Photo courtesy of the author

I have always felt that it was a shame, maybe that’s what is happening in the infrastructure of film, or the businesses of the agents and the publicists. I don’t have a publicist. I don’t think it is something that really suits. I didn’t really feel that comfortable with it and I thought it very expensive.

Wow.

I mean, I respond to the artist, the director, the storyteller in the room. That’s what I respond to, whether or not there is a lot of money involved and it does not really bother me, it never has.

So it’s an equalizer. You know that you are there to work, and you know that you’re there to do your job, to interact with people in the most professional way.

On the set, you’ve got a crew, you have got actors and even on the really big budget films that apparently have enough money to cover all of these things – there is a limited amount of time to do a scene. If you’ve got all this, time is money, there are lots of people. I’m not sure that the creative flow works in that way. It would be nice to think that you could go with the momentum of the creative…

Somewhat modulated, as soon as you are there.

Yes. You can’t really measure things even in quantum physics, not everything. Some things blow our minds, they put a spanner in the works. God, you know, we can’t actually understand, we can’t control it.

Different directors, their personalities come through in their style and this is the nature of directors. So many people and so many filmmakers are not aware of the weight of a director on their actors. They believe that they are just a conductor sort of in the background. It’s amazing how many times we hear this. How many times we hear from people saying, “I thought a director sits there in his chair and yells, ‘Cut!”

No. It is the vision, isn’t it? I mean, look at some filmmakers around: they have a real signature, like Noah Baumbach. He did Marriage Story and The Meyerowitz Stories with Dustin Hoffman. He also did…what was that film? Mistress America with Greta Gerwig. Greta Gerwig, Noah Baumbach, The Grand Budapest Hotel by Wes Anderson and There Will Be Blood by Paul Thomas Anderson, all these guys. They really do have a style. [What] it seems to me that they have a unique story that is beyond kind of anything that the industry would like to…they have rules and regulations and they are allowed to do things properly. They seem quite radical in their sort of approaches, I feel.

Bille August’s style seemed very unusual while I was watching Les Misérables.

Yes. Bille August was very caring, very supportive, and I think that’s a brilliant aspect of a director. They cast you. They think you are the person who can play the role, in that case, it was ‘Marius’ and they just kept behind you. It is almost like a manager, a football manager with his player. Even when you don’t believe in yourself, they’ve somehow got your back. Do you know what I mean? That is really nice to know when you really feel you can fail and you are okay. It’s not like you are going to fail and they go, “Right, I’m getting another actor”. It’s just nice to know that because we are human, we like to feel that we do not always have to be getting it right.

Failure is the best medicine.

It can be. It can be, you know, liberation or a gateway into true collaboration with the director. You can kind of really start to work together as a team. Sometimes you have to go through it a little bit, but it’s not always – getting to know people is not always easy. But you have got to be prepared to go through that, it may be.

Was Les Misérables your breakthrough moment? Or was it really Mojo or Tube Tales?

I think it’s all of them, really. I would say Mojo was probably a real breakthrough, because straight away I was in the heart of a London theatre with some really great actors and a great writer – learning my craft from some really good actors and Ian Rickson directing. In fact, it would be quite important for young actors to be amongst these kinds of people when they are starting, because you do learn a lot. I just had a very small part in the play, but I was watching how people did their job and it was a learning experience. I was kind of guided by these guys.

Regarding Les Misérables, you had a great deal of visibility very, very quickly. Was it disorientating?

Certainly. I mean, to be honest with you, I was not that comfortable with myself at that stage in my life. I was only 21, something, I can’t actually remember.

1998.

So I am 44 now. Years. A long time ago.

Nonsense. It was yesterday. [Laughs]

It was! Yes, exactly. I am kind of quite glad in a way that I took a step away from things. There was a lot of expectation, [and] you were sort of told, “This is your moment. This is great. You know you’ve got to do this you’ve got to go there”. People pushing you towards things, but I had no idea who I was. I wasn’t comfortable enough in my own skin to be grounded. But the stuff outside of me, how it changed my position in the business and all of that kind of stuff. I would be coming out of drama college, which was quite a sheltered environment, but they teach you how to do things properly. You have to go through the creative process, takes time, and you don’t get to creative places necessarily very quickly. I mean, there is no absolute kind of way to these things.

No prescription.

Absolutely. You were taught to do things properly and it’s in stages over weeks that you develop a character. In an audition, in the business, a lot of people expect you to arrive very quickly at heightened creative states. I’m not sure – some casting people do, but not all casting agencies and producers understand the craft. We don’t need to get to heightened creative states too quickly just read it, just read the scene simply from the page. There is nothing more to do. Let’s just get to know each other a bit. Do you know what I mean?

It doesn’t have to be an engineered process. Doesn’t have to be too many cogs in the wheel.

Once you get this feeling, this expectation that you somehow you feel the pressure that you have to get somewhere too quickly and it is just not possible. It’s not natural. I think they could actually do a study on the brain on how long it takes for you to read the lines of the script to where this becomes second nature. You are not thinking about the lines, you are able to use another part of your brain, which is very creative because you are able to think on many levels. You are not just thinking, “Fuck this,” then next line, because that’s not a creative set. That’s panic and you get through and people might think it is watchable. The potential for things to be discovered is lost. That’s the joy for me, the discovery of something new in the moment with the other actors and the director.

Now, if you’re under pressure to get that right, you’re given the script on a Friday by the TV company, you’ve got to shoot on Monday, all you are thinking about the whole weekend is this line, that line. You are not thinking about all the different layers that could, you know…Like I said, it is not an exact science. What I’m saying, on the whole: we should not rely on people just having to pull it out of the back. There is actually a craft. And that’s what I feel is not always acknowledged and respected by the people in the industry.

Watching Les Misérables felt empowering. Like, humans triumphing over absolute misery, over deprivation. Then I see something like Bodywork, which is this beautiful little farce and I feel like it’s comedy triumphing over just the sheer banality and everyday corruption that we face.

Yes, yes absolutely. I mean, all these things can be tackled. One of my favorite films is I Heart Huckabees because they tackle existential, metaphysical, spiritual stuff in a very comical and enjoyable way. But it is actually, you know, this quite a serious subject. You could also play…you could also be some really dark, strong, you know what I mean?

If you wanted to.

If you wanted to. My preference, nowadays, is to go more for the comedy, for the light. I am more drawn towards a lighter way of telling a story, if you can. There’s so much darkness, but then I am more than happy to go to pain, color, sound. I mean, I love music. I love all the spectrum of it all. It is really nice sometimes to feel the light come in, but I am more than happy to bathe in more melancholic tones of colors.

I listened to your music (specifically your album, Sail The Sea), for the first time the other night. Please tell me that you had this twinge of excitement recording at Abbey Road.

Yes. Well, I loved it. We mastered it at Abbey Road. Actually, we did not record it there. We mastered it, which was great being there for a couple of days. It was just an amazing experience. So me and my buddy, we were just so over the moon by then. Especially after all the hard work we have done recording, mixing. To be honest with you, there are a couple of music projects that I am involved in. Just finished one with my father, as well, called The Healing Waves and it has just been…I am so happy doing this stuff. It’s just, it has always been a dream of mine to record the songs that I’ve written over the years, just getting it out there and fulfilling that part of myself has been rewarding, really rewarding.

What do you think was the hardest part in approaching music in such a forward-facing way? What was the hardest part?

The hardest part. Well the thing is when you are writing or creating, making movies, it’s a collaborative process and usually, you can’t do it on your own and you have a lot of ideas about how you would like things to sound or look. I’m sure every filmmaker goes, “I would like it to look like this” or, “The music would be great if we had some strings here or we had this there”. And I think what that can do is stand in the way of actually just getting it made. So you have to simplify what you are trying to do and bring it down to its essence and trust that the essence of it is enough. So the simplicity of a song you sing, that’s what matters whether it has this stand in the way of you ever getting anything done. So you have to accept the limitations, but be empowered by the strength of what you are initially trying to say.

Do you think that you ever received a particular piece of advice that was helpful for you for making that transition?

No not really, nothing that I can remember. There were probably many people and many things were said over the years that I’m sure influenced me in every possible way. Nothing that stands out.

What was the worst piece of advice that you ever heard?

Oh God. Probably most of the self-help books that are out there, because I think that they put people in the dilemma that they have to try harder and be a better person and it’s a vicious cycle that just never ends because you get into this trying to be a better person and it’s exhausting. So there is nothing that you need to do in order to be loved more. How hard do we want to try, we just try, try, try. Don’t get me wrong, I like to work hard, I really do. Everything that I do, I will always…I enjoy working. I enjoy doing the things that I love, tell a good story, be a part of whether it’s playing on someone’s album, making my own music. But, there’s nothing more beautiful than just being accepted for who you are without any effort. That’s amazing.

The journey from acting into this sort of hybrid practice of both acting and music – has it been difficult, gratifying, both?

It has been difficult because there is only – the business sort of demands, certain attitudes to work, there are only so many stories and scripts that are around and it is really quite difficult to get good work. Really, really hard. I do not want to put it in a competitive term, but it kind of is. No matter how hard you train, how good you get in your craft, finely-tuned an instrument you might be, it makes no difference in getting good roles or parts because it’s just not about that. It’s about a lot of the times whether you’re on a list of people the producers would like in the film because things have changed.

There used to be low-budget films, middle-budget films and then your Hollywood blockbusters. The low-budget films with new filmmakers, new actors, new screenplays there was this experiment bit. Do you know what I mean? There are ten films, maybe ten or maybe a couple of them will break through, but we are prepared to take that risk. But you just feel all that risk is kind of gone. So everything is about, you know it has gotten harder to be involved in good things. So I have started to look for other places to express myself.

I was listening to parts of The Healing Waves. The sound felt crisp. It felt like the outdoors. It felt like the sparkle of nature.

The thing is that, you know there is…things are measured aren’t they, on success and numbers and things like that, but just me and my father just making an album was such an amazing experience. And it’s like, what do we need? Do we need somebody else to tell us that this is…people tend to think that it’s somewhere else, but you can make it happen. But you know what? I think the problem is making money. It’s quite difficult to make money. It appears so because people are streaming, there are streaming services, people do not really buy CDs, in general. So it’s kind of accepting as just the way it is and doing it for the moment until we explore ways that, maybe, we can be more successful on that level. On a financial level. I think it’s really important to don’t get too downhearted and just carry on creating. We need that, don’t we?

To a student, a young artist, musician, actor, filmmaker who has just come out of their MFA program, no idea how to proceed – what would you want them to know?

Just go out. It’s okay to get it wrong and learn from the people around you and get involved in something, it might be in a low budget theatre, I do not know. Who cares where it is, it might not have a high profile, but there will be people telling a story and you can be involved and it’s meeting the people that is just as much a rewarding experience as something else. Just getting to know…Interaction with others. It’s a collaborative process. It is not always easy, we have a lot of ideas about how we would like things to look or sound or whatever.

Come back to the essence and if you do need someone just come – go about your business slowly, do not expect too much too quickly and the big break. People looking for a big break with a big company, they do not necessarily have the answers for creative, you know creative inspirations. They are just making films. I mean, I’ve been involved in big films and I felt, “My God, this is just so far away from whatever,” you know?

From any grounded or cemented experience that you want to like move forward with.

Exactly. I mean, things have changed a lot since I started. Everybody has knowledge of films, everyone has a camera, don’t they? A YouTube channel. Technology has advanced so much and you can make a movie with your iPhone, you know? I think I have Ron Howard in one of his master classes talking about what really matters is what we capture between the…

Quality versus quantity.

Focus on that. You can never really stop learning about your craft and the more experiences with being in these environment is going to help. The other thing is, I do not think that we have to accept that we are not in control of everything. So a desire for a result can sometimes overwhelm the possibilities that might be there, you might think it has to be a certain way, and it can kind of obscure and the magic might be happening somewhere else. You’ve got to keep a little bit of openness to what’s happening in front of you.

This interview with Hans Matheson appears as the Cover Feature of our Summer 2020 Issue. Click here to purchase.