“The Most Overhyped Human Emotion”: Signe Baumane on My Love Affair With Marriage

Signe Baumane calls romantic love, “the most overhyped human emotion.” Her latest film, My Love Affair With Marriage, also concerns itself with love, but takes a more cynical–and humorous–outlook, drawing on Baumane’s own philosophy towards and experiences with love.

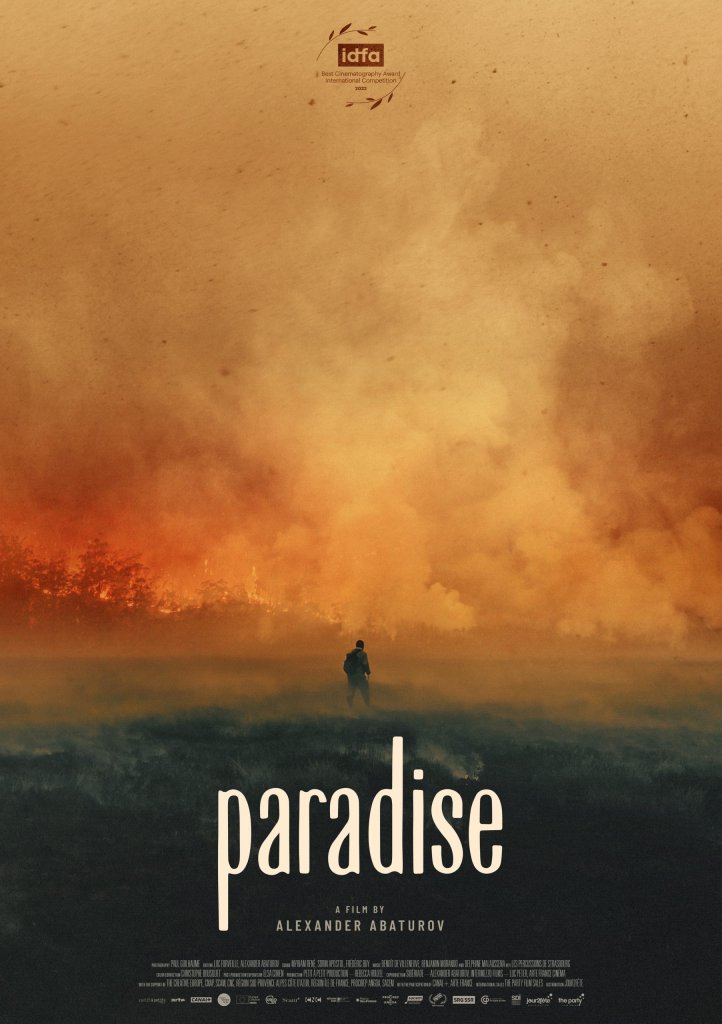

My Love Affair With Marriage follows its protagonist Zelma as she navigates sex, love, and womanhood, as she comes of age in the Soviet Union. Interspersed with satiric musical numbers about love and immersed within an animation style that mirrors the imperfection of humans, Baumane’s film presents an unapologetically contrarian stance on love and marriage. The film will premiere in the United States on October 6.

Frontrunner chatted with Baumane about integrating science into her film, the messages society tells women about love and marriage, her film’s unique animation style, and the future of gender equality.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired this film?

It was a long road. As an artist, I slowly understand what are the things that interest me. I made a lot of short films about sex, because sex is an interesting subject to me, and then I made a feature film about depression. My previous film is about the 100 year history of my family’s women’s depression and suicides. It’s a funny film about depression, so you don’t have to worry about it. In my new film, I thought, let’s combine the two topics of sex and depression. So I decided to make a film about marriage. For me, marriage is an interesting subject. It’s connected to so many things. But the main inspiration from which the project sprang from was the making of my previous film Rocks in My Pockets. I was writing a blog at the time and in that blog once a week I would put up a story. At some point I ran out of stories and I started writing about my second marriage to a self-described gender bending man. I thought it was a really dramatic story with secrets and cultural misunderstanding and everything. That was a really popular short story series. I wrote about 12 installations of the story. I thought it would make a great film, and that’s where I started to develop this idea. But then as I started writing the script, I was like, “okay, but why did we want to marry? Well, because we were in love, but why did we fall in love? What are the forces around us that formulate for us what falling in love is, how to frame love, and why love leads to thoughts about marriage?” I really wanted to dig deeper. That’s where I started to unravel this whole mystery of love and looked at biology.

On the note of biology, I found it really interesting how you included that as a character in the film, because in many films about love and relationships, you don’t really hear about biology itself. The films are focused on feelings, but not the science behind those feelings. Could you talk a bit more about why you decided to include this scientific perspective and why you made biology a character in the film?

You know, it’s funny, I just recently pulled out the script for The Wolf of Wall Street. In it, in order for you to understand this film, you needed these snippets of explanation about things like how financial structures work and what caused the economic collapse in 2008. Otherwise you wouldn’t get the essence of the film. I did the same in this film, but I didn’t exactly want to explain or teach or be didactic so I created this character. We are all biological creatures and biology happens every time we do anything. Right now in our brains there are all these signals going on and we of course don’t see each others’ brains work but we are aware that something is happening. I wanted to convey that simultaneity: you fall in love, but there are these other processes at work. In animation I can do anything. In this film there are four worlds where Zelma lives. There’s the real world where she lives with the three dimensional backgrounds and then there’s her fantasy world where everything is in her imagination and how she processes the world. The third one is political maps, and then there is biology. For me, because it’s animation, it was really easy to create: biology is a character, and she’s shaped as a neuron, with axons and dendrites and so forth. Writing the science parts of the script was very difficult because I’m an artist and I wanted to get it scientifically correct. I didn’t want to make just something close enough, I wanted to be very correct. So I worked with three scientists to get it right. When we had the premiere at Tribeca Festival, one of our scientists, Pascal Wallace, got up and said, “ladies and gentlemen, this is the most scientifically-correct film I have ever seen.”

I thought the animation style of this film was quite unique and something I hadn’t seen before. Could you talk a bit more about how you created it?

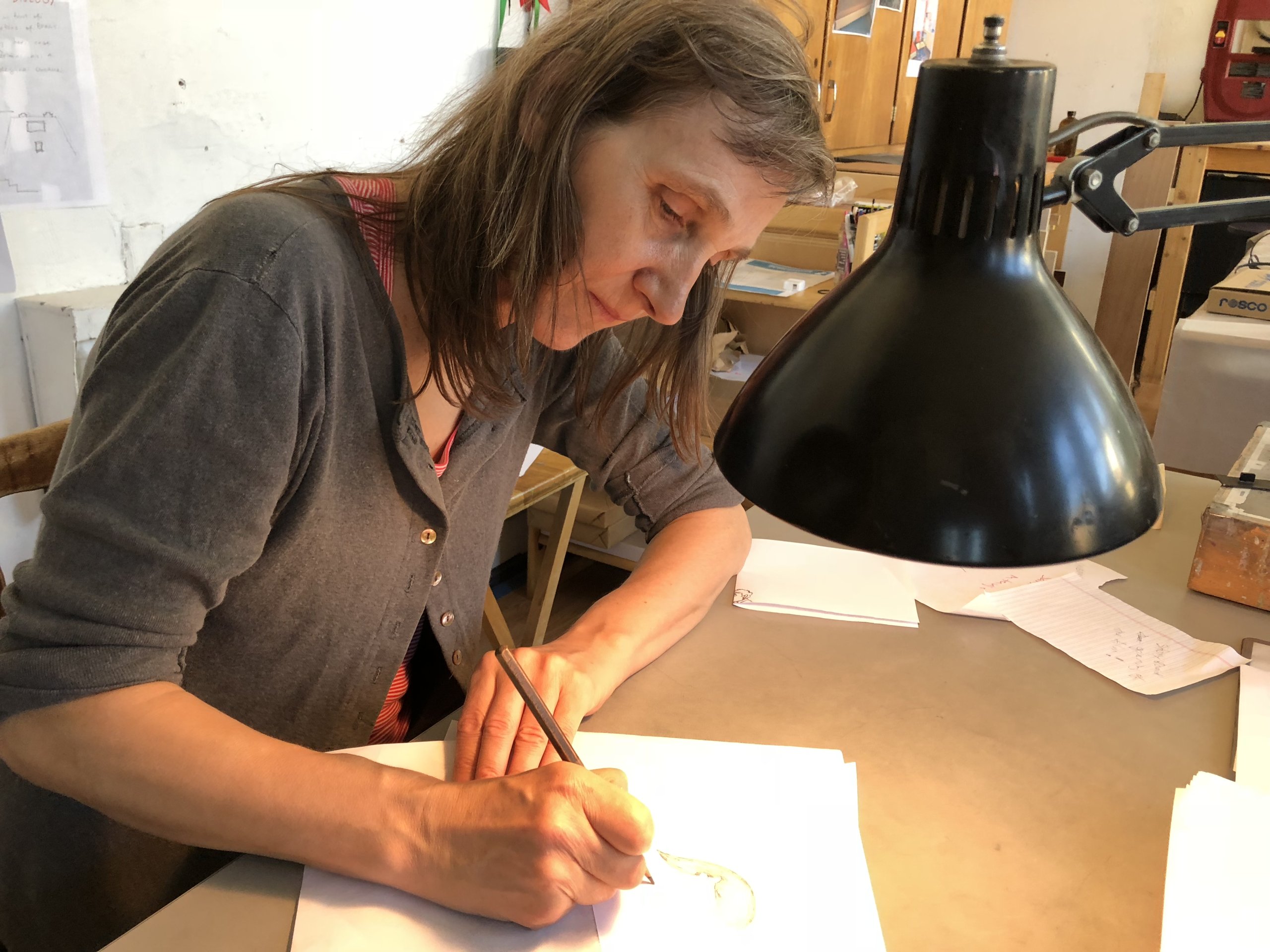

I never studied art. I’m from Latvia originally, but I studied philosophy for five years at Moscow State University. The way I draw or make art is like handwriting. I never learned to do it properly, so I do it the way I feel it. It’s a direct expression of what I feel; I aspire to express something inexpressible. But there is, of course, a time when as an artist, you reach your limits of what you’re doing and want to break into another way of doing things while still keeping your artistic integrity. And so one time, maybe, 15 years ago, I was invited by a fashion designer in Italy to make paper mache sculptures. I had never made paper mache sculptures before. As I was making these paper mache sculptures, I thought, this is amazing. I didn’t know I was able to do this amazing three-dimensional work. I thought I would like to incorporate that in my work. I just didn’t know how because paper mache doesn’t bend, so it cannot be a character. But what could it be? And then I thought it could be a background. So I created my first film, Rocks in My Pockets, using this technique. I created three dimensional backgrounds and I photographed them, and then I drew the characters inside. But My Love Affair With Marriage is definitely a more ambitious project. It took that one technique and it went deeper. It’s more developed, where we build these sets, and then our assistants, Yasmin and Sophia, used paper mache to cover it all. That creates a texture, and then they paint the first layer black and then paint lighter and lighter until they create that effect where the texture is revealed and it looks interesting. Then we bring it to the shooting room and photograph these sets. Then I take the printouts and draw the characters on top. I wanted to have that feeling of the sets and characters being manually created because I think we have so much digital in this world, everything is digitally perfect. I wanted to make a film that looks less perfect because one of the film’s themes is also what it is to be human. We are imperfect, that’s for sure. And also how marriage is a human-made concept, and love is also a human-made concept based on our innate biological needs. So it’s a visual concept that revealed a little bit of the ideas of the film.

That’s really interesting. I had no idea that the backgrounds in the film were actually photographs of 3D sets.

There’s another set I wanted to talk to you a little bit about, the one from the opening scene with the crooked buildings. The reason why we created them all going different directions like this was because the opening scene happens in Sakhalin, which is an island next to Japan, and they have permafrost. In the summertime, permafrost melts. So in the wintertime, people build their structures and they’re straight. Then in the summertime, the permafrost melts, and one edge of the building sinks into the ground. So when you go to Sakhalin, at least during my childhood, all the buildings lean in different directions, and I thought that was interesting. But it also reflects on the main idea of the film: culture versus nature. Our nature is this ground and we build these structures on it, like marriage. Then nature melts a little bit and our structure sinks and that’s why marriages are impossible for us because they are so constraining. So, our ideal structures that we created for ourselves are not really fitting with ever changing nature. I am not against marriage, but I’m always questioning.

Tell me a bit about the Mythology Sirens. I found their inclusion really interesting. Why did you decide to make this a musical with all these songs and include these sirens in the film?

When I was writing the script, I wanted to illustrate this tension between our nature and our biology and the pressures of society. Biology is easy: it’s a character based on a neuron. But how do you show the pressures of society? And then I was thinking, how did I get these ideas about what is love and how to love? I got those ideas in songs. There are love songs everywhere. You turn on the radio and every song would come at you and most of them are about love and or relationships. Love or hate or I’m free or I’m not free. It seems to be a big staple of songs. So I thought, well, if this is where we get our ideas, how we are going to frame our love relationships, right? It has to be a song. It has to be through singing characters. And of course, in mythology, the sirens are the ones who lured you away from where you wanted to go. You are on your path going somewhere, and then they lure you away and then your boat crashes against the cliffs and then you die. That’s why they’re mythology sirens and that’s why they’re singing. I created the sirens and lived with them for a long time–because it took seven years to make the film–and I often listened to the songs that I heard in my childhood from the 70s and 80s. And then I would think, this is an evil song. What is he singing about? For example, in Barbie, where the guys are playing guitars and singing the song, “I want to push you around, blah, blah, blah.” I never thought about what the song is about. Never. I just accept it’s a song about love and he wants to push her around. Suddenly in this context, I was like, “Oh my God, it’s an evil song.” There’s another Bryan Adams song from 30 years ago called “Please Forgive Me.” Back then when I listened I was like, “oh, he loves her so much, why doesn’t she forgive him? We should all forgive each other, right?” And then I listened very carefully and realized, “oh, yeah, he betrayed her, and now he wants to ask for forgiveness.” That’s an evil song.

I never thought of modern love songs in that way. I can definitely see how what you mean is represented in this film: the songs in this film are sung quite cheerily, but have these quite sinister messages underneath the surface or even directly in the lyrics.

Exactly. I think that’s what I like about the songs in this film, that because the message is so direct, it makes it so absurd. They say things like, “marriage is good for your sleep.” There’s a lot of elements in the songs that accent the absurdity of our ideas and concepts about love and marriage.

Yeah, I feel like the fact that a movie like this is being made and is as celebrated as it is shows that as a society, we’re all aware of what the world expects of women and the roles that it forces women into. But the film is still being made. So we haven’t really moved past those roles completely.

I started writing the script in September 2015, and at that time I truly believed that next year we may have a woman president. I thought with all sincerity that the film that I was working on was going to be redundant. It’s going to be unnecessary. And then what happened afterwards? It was shocking. The film is relevant and unfortunately it does make sense that it exists. But yeah, it shouldn’t. A film like this shouldn’t be relevant. We should be past it.

What kind of progress do you think still needs to be made to get to a point where a film like this would ever be relevant or necessary anymore?

At viewings, I always ask people to stay for the end credit song. I tell them, the song will answer all your questions about what you’re supposed to feel or think, but it also gives you a feeling of hope and inspiration for what the world could be. When I was writing the lyrics for the song I wanted to put in the ideas of what I wanted the future to be: parity, equality, happiness, inclusiveness, what would that be like? I started wondering, why can’t I come up with a clear idea of how I would like to see the society be organized? Then I realized that if we cannot have a vision about it, if we don’t imagine our future today, then we cannot make it happen. Then other people decide for us what the future is going to be. It’s like when I make a film, every day I do a little work that is not directly related to making the whole film, but all the little things add together because I have a vision. We have to have the same kind of a blueprint of vision for [attaining] true equality. What is it that we imagine? Then we can do that work today to achieve it. I lived so long under patriarchy in one way or the other–I’ve lived in the United States now for 30 years, and before that I lived in Latvia and the Soviet Union. I feel that I’m not qualified to have this vision or talk about it. I think that a younger generation, who lived less time under patriarchy, who may have more fluid vision of what it could be should have this vision. What do you want? How could it happen and then how could I be an ally and help make it happen?

With this film, do you have an intended audience? If you did, are there any particular messages you want them to take away?

The audience that the film is going out to is to anyone who has ever felt in their lives to be different, like the people who felt that they were not accepted the way they are. So that could include anyone, it could be a woman or man or anyone who has not felt accepted. And I think that’s a lot of people. When we screened the film, of course, the majority of people who really connected well with the film were women. We showed the film in Turkey, in India, Latvia, and all over Europe in over 90 film festivals and even in China, South Korea, and Japan and women are just like, “oh my God, that is my story.” So women are the core audience for the film. But men would also come to me after the screening and say, “I know I’m not a woman, but I really related to Zelma because I felt the same, you know, being made fun of like that.” You are different and grappling with understanding how to live your life when you’re different, you know?

What’s next for you?

I’m writing a script for my new project. When I was writing My Love Affair With Marriage, I said I will never, ever make anything that has science in it. I thought that would make it so much easier, because science is so hard. I was hitting my head against the wall when I was doing the science writing. But this story is also very hard because it’s also very epic. My new story is called Karmic Knot, and it’s about a family who lives through the collapse of a country. It’s very epic. It spans about 60 years. I wrote a lot of notes over our ideas over three years during the post-production of My Love Affair With Marriage. And now, I have all these notebooks and I have to narrow them down to a script. And I have to say it’s hell. But I’m excited I’m starting a new project. The filmmaker’s work never stops.

Responses