Doran Danoff & Edward Symes: Black Magic Piano

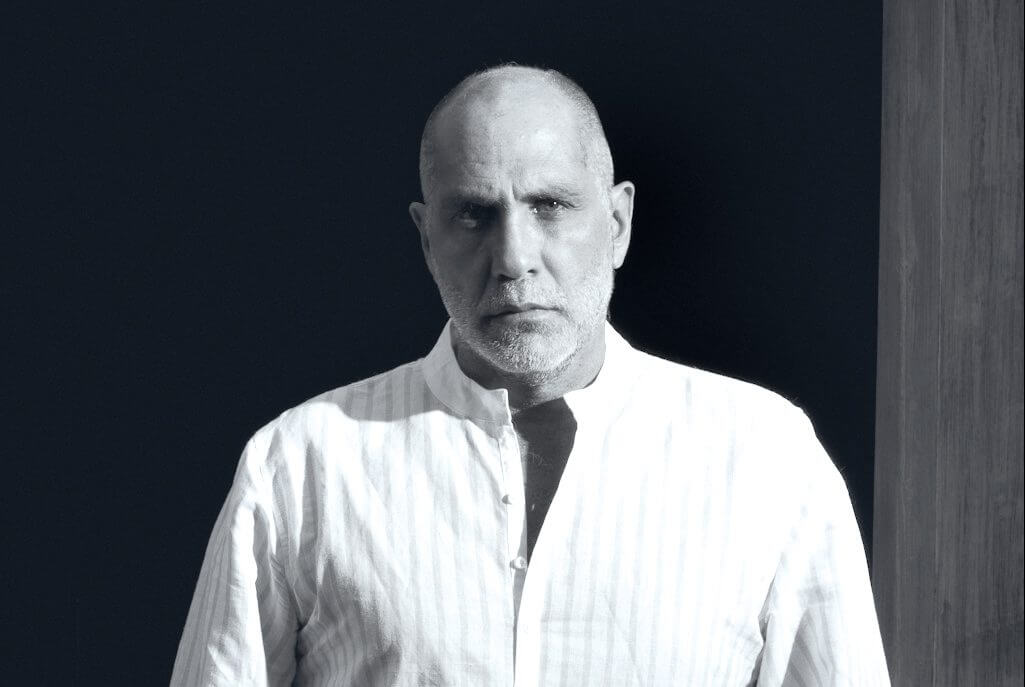

Teddy Symes was just a child when he first picked up a guitar. Inspired by his brother (musician, Nathan Symes of Chapel Hill) and other gruff, brooding vocalists (Tom Waits, Nick Cave, and Leonard Cohen), Symes always kept music near and dear to his heart. It was documentary filmmaking, though, that ultimately won his favor. Symes wouldn’t express himself through music until he moved to New York in 2009, when he found himself sharing a small studio apartment with an enormous grand piano. Symes arrived in the big apple after a break up and having lived several months on the road. He’d been shooting videos for the Obama campaign and a labor union in several different states, and his arrival to New York marked the first time he’d been stationary in a long while. The filmmaker settled into a fourth floor walk-up in the Village, where he was able to reflect on movement, the city, and his recent break-up. The studio apartment was dominated by a giant grand piano that had once been housed in Rockefeller Center’s Rainbow Room. The piano’s mystery extended beyond the fact that it somehow climbed to the fourth floor of a narrow Manhattan building; it had an ineffable allure that beckoned to Symes and, in a single month, it wrenched 14 songs from the neophyte piano player.

After the sudden catharsis, Symes shared his music—which resides within that same Tom Waits realm—with Doran Danoff, a professional musician and an acquaintance from his alma mater, Kenyon College. Danoff liked the combination of the “simple” piano compositions and the descriptive “little vignettes of an experience of someone in New York.” He was impressed at the quality of the compositions, given Symes’ inexperience with songwriting, and, in jest, attributed it to the piano’s “black magic.” After fleshing out the arrangements and recording the songs at a Brooklyn studio, Danoff pushed Symes to reimagine the project as something more than just a musical EP. The scope should be larger, he thought, and it should utilize Symes’ skills as a filmmaker.

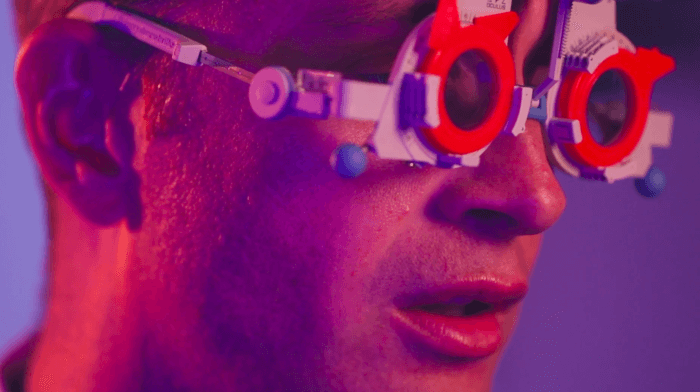

Soon enough, Black Magic Piano had legs as a multimedia project. Symes began probing visual mediums for additional inspiration, and he felt that elements of modern opera would fit the Black Magic Piano aesthetic. It was natural, then, to involve Danoff’s partner and now-wife, Elizabeth Wilkinson, a modern dancer and choreographer.

Over the course of six years, the trio edged Black Magic Piano toward completion. Limited funds and resources threatened to kill the project on more than one occasion, but they pushed ever onward. Through music, film, and movement, Symes pieced together a “universal story” of the struggle to make art in New York City. Though not strictly autobiographical, the project certainly bore similarity to Symes’ life, and as the creative process wore on, Symes’ resemblance to his fictional protagonist, McNair, grew more and more apparent.

That kinship between character and creator makes Black Magic Piano feel both relatable and authentic—an honest ode to the unforgiving and singularly beguiling New York City art scene. 7/8 of an iceberg remains below water, forever inching toward the surface, half drowned, as the tip slowly melts; the same is true of New York City artists. As such, Symes and Company stay true and place colorful overlays of statues, bridges, and other iconic NYC ephemera side-by-side with the city’s more lackluster trappings—the cockroaches, the dollar pizza slices, the cheap ramen, the endless search for a few extra bucks.

Holding together our portrait of the city is, what else, a love story. Over the course of 40 minutes, McNair and his lover experience love’s initial ambush, domestic partnership, and, finally, the complications and estrangement of trying (and failing) to know another. Black Magic Piano is as open as the wounds and wonder that inspired it, and it’s as inviting and as beautiful as the piano that originally wrested the story. Music, film, and dance merge seamlessly into a multimedia event that disregards convention in favor of truth.

Now that Beyonce’s Lemonade has arrived, there’s some precedent for an episodic visual album, and that may play a role in determining how the project is eventually received. On a conference call with Danoff and Symes, we talked about the ongoing search for Black Magic Piano’s home, as well as the demanding DIY processes that all coalesced in its final form. One thing’s for certain: this is art for art’s sake, and, as such, it bears the souls of its creators.

Teddy, can you talk about when you first moved into that apartment and began writing songs on the piano?

T. I brought my guitar with me to New York and I wrote maybe one or two of the songs first on guitar, and then I thought maybe I could figure out some really simple chords. Just to try to structure the songs, and I found that the rhythm of hitting the keys really worked for me as far as trying to write words to the chord formation. And they just started to come out. I think I wrote 10 or 12 songs in a month. It was just waking up in the morning, pouring some coffee, and sitting down at this piano and seeing if anything stuck. And if it didn’t stick, I would just walk around New York. I was kind of nomadic at the time. Just to have a place to be was kind of a luxury for me, just to have one place to stay. I think the combination of moving for a while and then being in one place with the piano gave me the opportunity to meditate on a broken relationship that I had just gone through.

Once you had the songs written, at what point did you bring them to Doran? What was the next step after that?

D. He played me the tunes and from the outset I was really into it because of the fact that he wasn’t a piano player. The way that he was writing these songs on the piano was so juvenile and simple. And the lyrics were so descriptive, like a narrative in a way. The combination of those two was really intriguing to me.

T. It was very DIY, basically just a laptop and a couple of microphones. We basically decided we wanted the sound of this old piano. There were times when you would hear these unique sounds from the piano that were not necessarily clean.

D. It was definitely out of tune and honky, but that was part of the character of it. It was a very unique sounding instrument. It wasn’t pristine. It wasn’t an elegant grand piano. It had this vibe to it that we wanted to capture.

T. You’d hear the steam coming up the pipes to heat the building in the middle of the room, and you’d get these weird sounds and it was very ghostly. We had no idea what we were going to do with the songs at that point. I mean talk about an organic process—it took almost six years to develop it, but it reminded me a lot of a documentary film because a lot of the time you just have to have that leap of faith. If you start the ball rolling and moving in some direction and let it guide you, it will come together.

So after you fleshed out the songs and it started gaining some form, what was the next step?

D. We had the arrangements in order. We had 14 songs, and I put together a band of some great players I knew in New York. We found this studio called Seaside Lounge in Brooklyn. It was like a poor man’s good studio. And we went in and cranked it out. We did it in three days of full band sessions and it turned out great. We got some really good stuff. And then from that point, that was ground zero. Having the music was just the beginning of the whole thing. We had the bones. We had the framework to make it happen.

T. I remember deciding that we really wanted to make it feel like it was played by a live band. We wanted it to feel live to have that vintage feel. We had these great musicians that Doran was able to attract and we said, ‘hey, we’re going to play this live in the studio.’ It was really just trying to capture lightning in a bottle. Doran is such a strong bandleader, so we were just trying to capture that feel. At that time, he was the music maestro and I was seeing the music in colors and shapes and stories and more from a visual standpoint.

So is that when you decided to add a visual element?

D. We were having a conversation about going to the studio. That was Teddy’s idea. And then I said to him, ‘what’s your intention here? You’re not a musical artist. You’re not planning on going on tour.’ I was like, ‘why don’t we think of an outside of the box thing with this?’ And that was when we brainstormed about making the album into a movie.

So once you did decide to turn it into a film, how did the narrative arise? I know the lyrics were already there, and it’s about love and heartbreak. But did an overarching narrative arise from that pretty naturally?

T. It didn’t really happen very naturally. It was really tough for me to make this film because there are a lot of elements that are autobiographical and a lot of stories from friends of mine, who either have slept in their studios or have almost been homeless in New York so they can keep making their art, or they take really weird jobs. I listened to the songs and I just started living a life in New York. I think we were just learning a lot in that period of time. I felt like I was learning something new about the city every day. I didn’t really want to make the film about my own experience, so I started thinking about a main character that arrived in New York, this universal story about how people move to New York and try to make their way, some of their setbacks, some of the challenges that they face.

D. Teddy was coming up with this script and we were working on this script together. But I think Teddy is understating that he basically lived this character. It wasn’t based on Teddy, but the deeper that we got in this project, the more the project became his life. He started driving a cab to raise money, and the character McNair in the film is driving a cab to make money, so we had access to a taxicab that we used in the film because Teddy was driving a cab to make money so he could keep doing this project [laughs]. At first this was a fictional concept, but the deeper we got into doing it with no money and just trying to figure it out, in this weird way, the character of this whole project became Teddy’s life.

Where did Elizabeth come in? She obviously played a huge role—at what point did she come into the fold?

D. Right around that time, Elizabeth and I had done a really big theater show, and we were really inspired and working together a bunch, and we were talking to Teddy and deciding what kind of movie this would be. We were throwing around the idea of it being an opera, this modern sort of whatever this was going to be. We looked at some examples, like Einstein on the Beach, and collaborations with people in this classic New York art film scene, mixing performing arts disciplines, and whether it would be movement or visual or music, so it became a natural ‘well, of course we should use Elizabeth and we should have dance in this.’

When you had this vision that it was going to be a documentary/album with elements of opera—were you looking around at the art landscape and realizing that there really wasn’t much out there like this? Was that an impetus for doing this way? Or was it scary because you didn’t have a reference point for where you were going?

D. We were talking about intentional concept. We wanted to define it because that was going to help us frame our work, but we didn’t see anything around us where we were like, ‘this is what it is, we should do it like that.’ We were just trying to do our own thing but have inspiration from similar concepts.

T. I felt there was a great opportunity to use our different disciplines to come together and make something unique. But I also think it gets back to that original meeting when Doran upped the ante for the project by saying, ‘look, this isn’t just a music album, you’re a filmmaker, you have to bring something to the table aside from just the music’, and that really opened up a whole world of possibility.

When I watched it, there were two projects that came to mind. It sort of has the love aesthetic and musicality of Once, albeit in a more avant-garde delivery. And then Lemonade, because that’s very episodic, like this is, even though the kind of music and dance is different.

D. Yeah it’s funny now that there’s been a mainstream thing like that. Teddy and I were talking about it when that came out, and it put this into a more relevant context now—not that they’re even remotely close. This thing is very out, it’s very avant-garde, it’s very art house. We just did it. We were just doing what we wanted to do. It was free. It was totally creative.

Responses