Faith Soloway: The FRONTRUNNER Interview

In 2014, hardly a year into the experiment of original prestige television that did not air on a TV, Amazon Studios premiered Transparent, a comedy-drama about a family dealing with the aftermath of a parent coming out as trans later in life, which was based in part on the real-life experience of creator Jill Soloway. Pitch the logline and you could be describing something better suited to the festival circuit, the kind of semi-autobiographical indie film made on favors and earning its returns only in accolades. But from the first season, it was clear that Transparent was something wholly original, human and boundary-breaking. Critics applauded the show for its craft and its landmark introduction to a trans main character just as much as they did for its rupturing of the rules of what a television show could be. Throughout its five season run, ending last month with a special feature-length musical series finale, the show has netted eight Emmys, two Golden Globes, a seemingly endless churn of press, and enough theorizing on its place in multiple canons (queer, Jewish, TV, you name it) to supply a graduate course. Throughout its run, it has continued to break form, and in the process, helped redefine for the rest of the landscape what is possible on TV. With its closing movie-musical, referred to by its creators as the “Musicale Finale” (pronounce the first as a rhyme with the second), this project of mold-breaking reaches its peak.

For the whole run of the show, Jill Soloway has collaborated with their sister Faith, a musician, writer and performer who began her career musically directing at Second City in Chicago. In addition to being a writer/producer throughout the series, Faith is the primary creative force behind the music which drives the finale. What began in 2017 as a hopeful stage musical performed across a run of Faith’s residencies at New York’s famous Joe’s Pub has now landed on the screen, refitted and expanded to tell the finale story. The near-two-hour musical film follows the family dealing with the death of Jeffrey Tambor’s character “Maura” (Tambor left the series in late 2017 after multiple members of the cast and crew accused him of harassment; Production was halted while the creators figured out how to proceed.) The movie-musical plays like rock opera meets big-budget stage musical meets finale special. The Transparent Musicale Finale, now streaming on Amazon Prime, is co-written by the Soloways with music by Faith and directed by Jill.

FRONTRUNNER spoke to Faith (who cameos in the finale as “Shmuley”, the musical director of the show-within-a-show) about the decision to sing the finale, Jewish influences, the use of humor when tackling serious issues, and whether the form of the movie-musical can still survive.

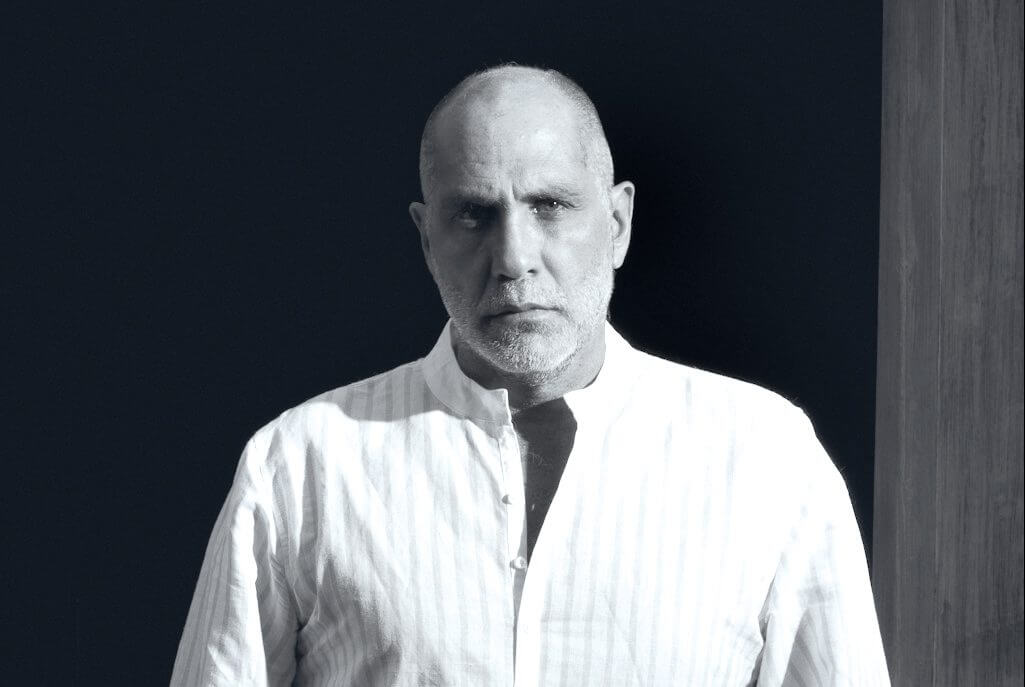

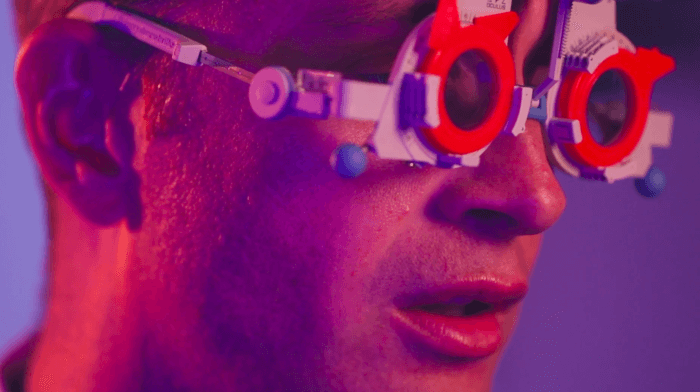

Transparent: Musicale Finale (2019), Dir. Jill Soloway

Image courtesy of Amazon Studios

At what point in the process of developing the finale, or the potential final season, did you and Jill decide that a musical was going to be the right form?

The music part was kind of always there, no matter what was going to happen, even for season five. Even when we, before everything kind of broke down. It wasn’t a for sure thing, but it was on the board. It was pitched that “Shelly” [Pfefferman, played by Judith Light] kind of returns to making something out of her life. And then everything kind of folded and there were different possibilities. But when we stopped in production, it was just a real stop. And the questions were, “Can we go on?” But, the next step was, well, does that mean the entire arc or the whole thing would be a musical or it would be, you know, episodes with songs? And then the more that we were just thinking about kind of coming back together as a community, more people wanted to sing and wanted to turn into a completely different direction. And Jill was always wanting to break form and start in a different direction as we tackled this. And so it’s an ode to the transition of the show and the changes and the healing and the potential to break it open and give a nod to the musical in a certain way.

The show has always been very Jewish.

Very Jewish. [The finale] is more Jewish than it is a musical, I have to tell you. It’s the most Jewish thing you’ve ever seen.

What was interesting to me was how much Jewish musical reference is in it. What was the inspiration behind incorporating the natural melody of Jewish prayer into some of the music?

It’s just there in being Jewish. It’s there in the journey of the Jew, in making your, the transition from a child to adult, and taking on the importance of scripture, you’re taught through those melodies. And as soon as we knew the story was, you know, Ali to Ari to Bart Mitzvah [a clever mashup of a Bar/Bat Mitzvah observed by Gaby Hoffman’s character, who came out as nonbinary in Season 4], it’s just, you have to go in that direction, melodically. When I was first tackling it, I kind of looked at this thing as two musicals and they meet in the middle, or they meet in the end. And that was Shelly’s musical and Ari’s musical. So Shelly’s music is in that minor to major kind of, even within the show tunes, she’s sort of lampooning the way that we can’t escape from our Jewish songwriting.

And even in the tunes that were more showtune-y I kind of stuck some of that melodic, you know, I guess a nod to Fiddler [On the Roof] a little bit. The Fiddler score is very much that, it’s like in the klezmer, the choices of notes and melodies and all of that stuff. So there’s really no escaping. There’s no way to play with hints of Jew in what we were setting off to do. You have to use everything that is in front of you and that you’re feeling.

You came from Second City and the Annoyance Theater in Chicago, and worked a lot in comedy musical and even musical parody early on. I don’t know if you would still refer to it this way, but you’ve called your style “Schlock Opera.”

Schlock opera is a good half of me. The other half is a pretty, you know, I like the serious, beautiful, sad music, as well. And when called upon, I love to be in that. I love to write a song from that space. I was doing the schlock opera thing as a way to make a name for myself. And it’s a more of a marketing thing and more of a true part of me that is clown, you know, and healing through clowning and expressing that love to other people. There’s nothing that feels better than laughing together. So, it was an interesting discovery for me because I’ve lived in both worlds pretty 50/50. I was a really serious musician when I was in high school, I was a cello player. And you’re not doing a lot of comedy tunes when you’re playing cello. I was a pretty serious piano student, you know. And then as the comedy stuff became endearing to me and I wanted to live in that world, I just kept both things going.

Can we talk about “Joyocaust” a little bit?

Sure.

(Note: The closing song to the film, “Joyocaust,” is a number bringing together its thesis of sorts: that humor and comedy often coexists with tragedy, and the power of comedy to help people cope with trauma. The title is a portmanteau and a tongue-in-cheek proposal for dealing with the intergenerational pain of being a Jew: a “Holocaust with joy.”)

Was there any kind of apprehension?

Of course. There’s always apprehension, but you can’t–apprehension means deciding not to do it. So what are you gonna do with that? You can’t really be subtle with it, with a title called “Joyocaust.” That’s another way that I was informed in my early adulthood, was shocking titles, but being able to own them and teach with them. So, “Jesus Has Two Mommies” [Soloway’s satirical rock opera about a young lesbian couple facing discrimination and meeting Jesus] was a title that I really wanted to get behind. I did that in 2000, in 1999. I was a lesbian wanting to have a child and the world was saying that it was an unhealthy thing to do. So, there’s always something behind the pain of what you’re trying to break out of. And the title “Joyocaust” actually was my sibling’s idea. Because I think there is this feeling of being a Jewish person, we are told never to forget so that it doesn’t happen again. And then what happens with all that “never forget” dark pain? It’s interesting, generationally. It seems that the people who are survivors were taught never to forget, but also never to look at it, to just keep going, because if you look at it, it’s too much.

It wasn’t for Jill, like, “Hey, catchy title, ‘Cannibal Cheerleaders on Crack’” or whatever. You know, it was just a real feeling. The most important line in the song for me is having Shelly say, “Hell yes, we crossed the line/And that’s why I’m feeling fine.” You know, “I can do it. I’m allowed to say this, and I need to say that.”

You’ve written on Transparent with Jill since the beginning. As a lot of people know, this show was inspired by your and Jill’s own experiences, even though the scope has grown from there. What’s it been like telling the story, which is in part inspired by family, and getting to tell it with your family?

Luckily, Jill’s well into adulthood in writing about this. But still, I mean, the feelings are so fresh. It just makes you kind of go back and look at your entire life in a much more profound way. So, there’s obviously a lot of conversation and I think we had to be tender in a certain way because for our parent, who we do refer to as Moppa, she’s just discovering things. So, she needs her own time, her own discovery process. And Maura is really not our parent, not anywhere close to really who my parent is. It was, you know, who we created on paper and knowing sort of what Jeffrey could potentially bring to the role. And yet at the same time, there was a little bit of something that was similar.

Transparent: Musicale Finale (2019), Dir. Jill Soloway

Image courtesy of Amazon Studios

It’s obviously a deep, triggering, illuminating, chaotic process when you’re writing from the hurricane of something that you’re going through. So, we just kind of tried to take care of each other through it. And also, that’s one thing just to write about your family and write about really how your parents’ journey affects you. But then there’s the other unexpected thing, which was how popular and how much attention the show got. So that’s the other thing that we really had to mine a little bit, with our parent who was out, but that didn’t mean she wanted to be out in the New York Times. So, I think Jill had to navigate how we would stay open with our parent about how much to speak of her and [sharing] pictures and all of that stuff. We sort of held each other’s hands the whole way.

For the finale, were there any movie musicals that you looked to for reference or inspiration, or that you drew on?

I would say All That Jazz, but to be honest, I don’t remember it that well, but I remember the feeling of it. But, there really wasn’t. We looked at a lot of different movie musicals and never said, “Ah, it’s this,” but I think we said it’s pieces of this, it’s pieces of that. It was kind of knowing what we knew and then going outside, drawing outside of the lines a lot. We didn’t have a lot of time, which, usually when you have something of this scope, you have a lot of time. We didn’t, so we couldn’t overthink certain elements of it. There were certain things we were capturing in a really raw, ragged way. Those were sort of my favorite parts. And there’s some things that we kind of rehearsed and choreographed over and over and over. You know that movies are sort of, sometimes they’re happy accidents, things that get caught, the magic that gets caught. And you’re so lucky that it turned out that way. There’s a lot of that in this.

Is there a movie magic moment where everything worked out really well that you love above everything else that made it in? Do you have any special, favorite moments?

Every time the prelude to “Your Boundary is My Trigger,” when the Pfeffermans meet the fake Pfeffs, and that little dance as they’re discovering that Shelley has recast them is kind of one of my favorite moments because it’s something that you can’t really write. The moments that happen in the air when you choreograph something and you sing something and there’s an emotional charge. That’s one of my favorite moments, and it’s all kind of there in the choreography. And Ryan [Heffington, the choreographer] was really great. Ryan and Jill really worked together to create a language. Ryan would maybe mark something out and Jill would, Jill’s very, very visual and feels things in a different way. So there was really great discoveries and an experimentation between the two of them. And then there were times where I was just fighting Jill, like on real basic stuff. Like, “The camera needs to be on the person that’s singing! The camera’s not on the person that’s singing, how are we going to feel it?” Because, you know, in “Joyocaust,” [the camera is] all over the place. And that’s like an example of like doing something really fast and just capturing magic. But also, I was just hounding them to get vocals on the camera. That was a time where we were a little bit under pressure of making a day and capturing this entire monster of a song. There’s so many different people singing different things at different times. And I loved it. For me, the best collaboration is actually disagreeing with somebody.

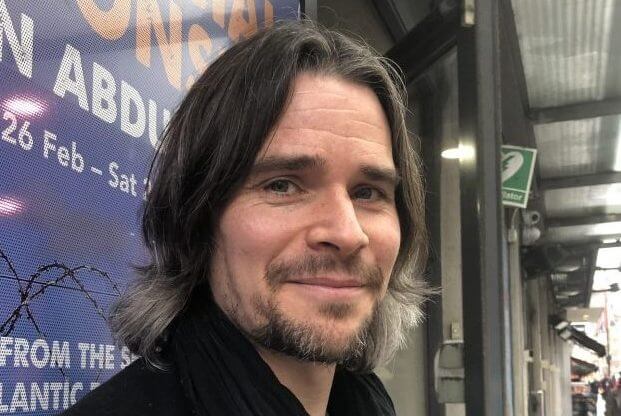

Image courtesy of Faith Soloway

The original movie musical on a larger scale almost seems like an obsolete form now. Do you think it can still exist on a theatrical scale?

Well, I’m noticing what people are doing, what’s being funded. I feel like it must be really, really hard to do this. You know, finding great songs and getting people to care about characters you don’t know, or songs you don’t know. That’s why people are going back to the old musicals. We want to celebrate that old time where we felt, “God, I love this thing I’m watching” instead of taking chances on new material. People are obviously writing the material all the time in movies and television, but music feels a lot more daunting. People are intimidated by the process. People can judge it so automatically. ‘Cause once you’re in a song, once you enter a song, you can’t get out. That’s kind of my feeling. You’re in this car or in this journey with this song and you’re either like, “God, I hate this. Get me out of this,” or “I love it. Keep going.” Where you’re in a scene in dialogue, you kind of don’t approach it that way.

I just know from working in comedy rooms, and comedy in general, people make fun of musicals all the time. I think there’s been a generation of musicals that have been so effective because they’ve been parodying the musical form. ‘Cause people are like, “Ah, I hate musicals and so does this writer.” From Spamalot to Book of Mormon. I don’t know who started this, but back in the day of old musicals, there was nobody winking to the audience like, “Isn’t this dumb?” I think there’s been this self awareness that’s kind of ruined the movie musical in a certain way and the chance for it, because it is about a romantic escape from reality. It’s really hard. The best musicals can break you without you realizing what’s going on. Because song can do that.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.