London Korean Film Festival Part I: The Stars Whisper

Hard-of-hearing Yeon-hee reluctantly starts at a new school. She makes an awkward first impression in class, garnering the attention of the fanciful Young-jin. When they bunk off school and spend the day together, an inevitable romance blossoms. Frolicking in the countryside, the two children begin to form an unbreakable bond, despite Yeon-hee hiding her disability from Young-jin. Only when he realises she is deaf does he understand the importance of the communication they’ve shared. It is a film that celebrates extraordinariness and tells an uplifting tale of overcoming adversity by being – above all else – true to ourselves. Born in 1992, director Yeo Seon-Hwa majored in Film at the Korea National University of Arts. She directed short films as It’s A War, Sayonara, and 3 Minutes To Go, a VR short film.

For the 2019 London Korean Film Festival, FRONTRUNNER interviews Seon-Hwa on her Special Jury Prize winner at the Mise-en-scène Short Film Festival: The Stars Whisper (별들은 속삭인다).

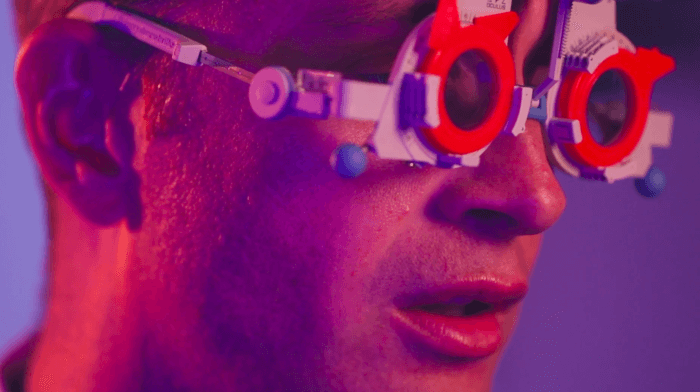

The culmination of a musical number with sign language choreography is wonderfully imaginative. How did you come to think of this scene?

First of all, thank you for paying attention to the combination of sign language and musical. This is a story that began in sign language.

When I went on a trip to Vietnam, I met a Korean deaf man there and he spoke to me. “There’s an American deaf man who has a lot of money, and he’ll buy you a drink.” I couldn’t resist drinking – I REALLY love to drink – and communicated with body language by text. This became a good experience for me and I wanted to film on the subject of deafness and sign language. I thought their sign language was similar to a beautiful dance. It could be my misunderstanding. At first, I thought of a dance musical consisting of sign language, but I designed a musical scene with both sign language and sign language for complete communication.

Dir. Yeo Seon-Hwa

What other films have influenced your project?

Musical films are rare in Korea. Especially in the case of short films, there is really no such thing. Surprisingly, I did not refer to musical films. But I should have decided between the grammar of the musical and the grammar of the film. It was really stuffy and confusing. So I just referred to the key points: the life of the deaf person and the communication with strangers, rather than the musical form. I referred to the French film La Famille Bélier, to know the deaf. Also, I referred to the Japanese film A Gentle Breeze in the Village, to know communication with strangers.

I started working with the composer by selecting several keywords in advance. “A warm, nature, an acoustic.” For these keywords, the instrument is minimized and we composed music using the piano as a major part.

To what extent is the film a personal endeavour?

Most short films are completed by the director’s efforts. But since it was a musical film, my own efforts were clearly limited. Because I was not an expert on music and dance, I tried not as a decision maker but as a collaborator. Once I heard the opinions of partners such as a songwriter and choreographer, I made the most helpful choice for the film. Sometimes we all had different opinions because the genre of short musical films was so unfamiliar.

For example, we had to decide the length of the number’s interlude. Music is built by an interlude’s enough length. But I thought that the interlude represents the color of the film rather than the progression of the narrative like the opening scene of La La Land. I thought that the scene was too long for the time allowed for our short story and that the scene not related to the advance of the narrative. I felt it is just surplus. So I asked composer to cut off them. The composer refused, at first, but soon she understood the practical issue to get rid of them. No one knew much about short musical films, so we had to face problems and fix them.

Dir. Yeo Seon-Hwa

How does the film expose and celebrate disability?

Dealing with deafness that I don’t know well gave me a big scare. I approached as carefully as I could. I was worried that my misunderstanding would hurt them. In the planning stage, the reason why musical scenes in sign language were reduced was because of the pressure of talking about what I don’t know well. In other words, my point of view is more projected. I once asked a sign language interpreter about the sign language of this piece; she said there was no problem with sign language, but it feels too beautiful for a real deaf person to sign. Maybe it’s natural. Because sign language was beautiful in my eyes.

In a word: I tried to deal with things I didn’t know very well, but I think the perspective of the person who can hear was projected.

The film seems to defy genre. It’s a bittersweet romantic comedy, a drama and musical wrapped up in one. Is it more challenging to fit all of these together in the limited runtime that you have? Does it mean every scene needs to be concise in its narrative themes or is there more of an opportunity for a freestyle kind of filmmaking?

I don’t know if I understood the question correctly. Let me tell you about the pros and cons of melting different genres of styles in a limited time. You’re generally right. I wrote quite a few scenes at the scenario stage, but I removed many just before drawing the storyboard. The criterion for scene removal was whether the scene worked organically in narratives. Thanks to this process, there is no surplus. There are many genres are mixed, but I was able to express one topic concisely. This restriction makes the creator find own style. However, if there is a regret, there was a comment that it seemed like the film was rushed rhythmically due to the limitation of runtime.

Dir. Yeo Seon-Hwa