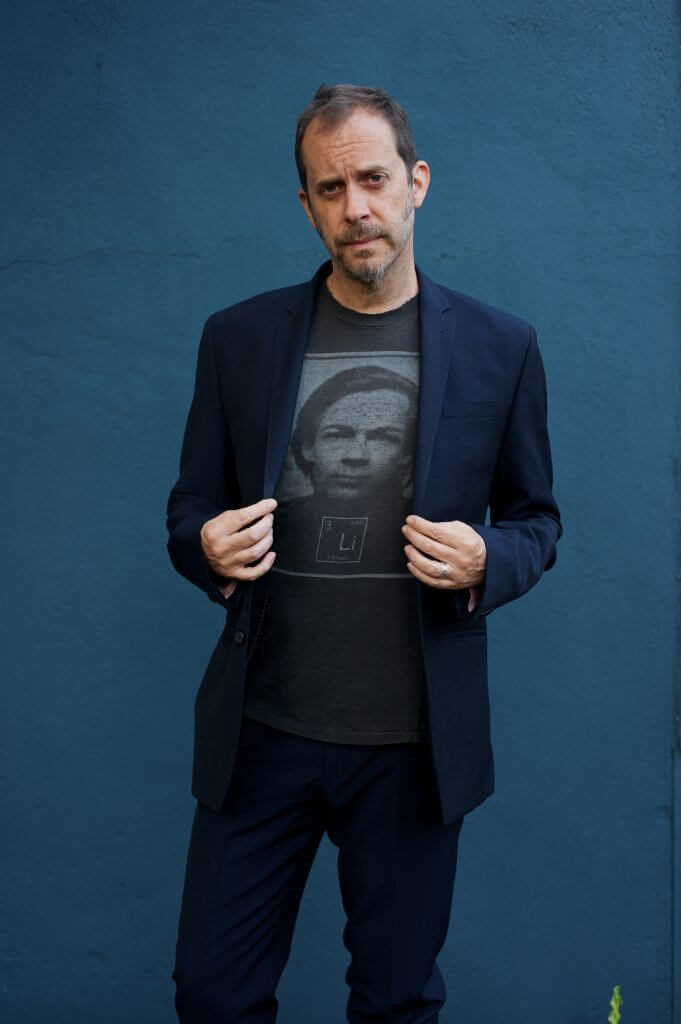

Tyler Hubby: Transforming the Documentary

Tyler Hubby has edited over 30 documentaries including The Devil and Daniel Johnston, a picaresque biography of mentally ill artist/musician Daniel Johnston. His editing work has earned a Peabody Award, countless film festival awards, and television broadcasts. His subversive and irreverent short films detailing fetishism, co-dependency and bodily mutations have screened internationally and are featured in the book Cinema Contra Cinema by British author Jack Sargeant. Tyler lives and works in Los Angeles. I interviewed him on his recent feature directing debut, Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present.

Tyler Hubby has edited over 30 documentaries including The Devil and Daniel Johnston, a picaresque biography of mentally ill artist/musician Daniel Johnston. His editing work has earned a Peabody Award, countless film festival awards, and television broadcasts. His subversive and irreverent short films detailing fetishism, co-dependency and bodily mutations have screened internationally and are featured in the book Cinema Contra Cinema by British author Jack Sargeant. Tyler lives and works in Los Angeles. I interviewed him on his recent feature directing debut, Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present.

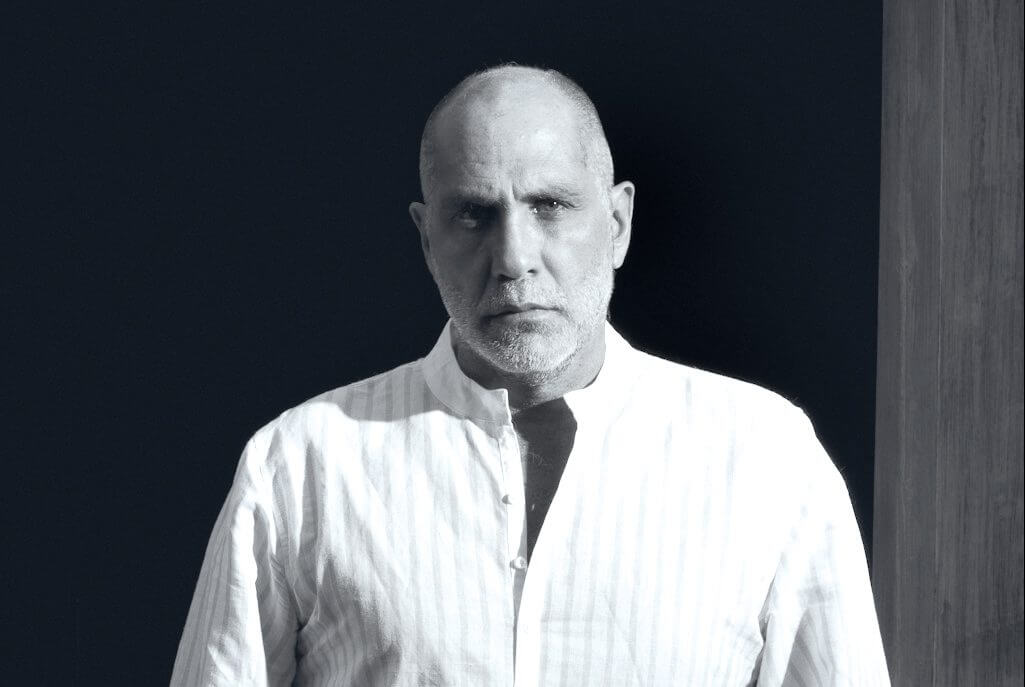

How did you first meet Tony Conrad and how did your relationship evolve during the production of Completely in the Present ?

I met Tony in 1994 when he started playing out in support of the re-release of Outside the Dream Syndicate. There were a series of dates in the US and I was along to document the performances. We continued to meet up over the years to record performances or interviews about certain topics. In 2010 I suggested that we turn this archive of materials into a feature length film and began shooting even more.

As a documentary filmmaker and an editor of documentary films there is a certain authority you hold in telling a person’s life story. Was this complicated or further inspired telling the story of an American artist with an interest in authority?

There is an implied authority that naturally occurs, although in this case I hardly think I am an authority on Tony Conrad. There are so many writers and curators and even collaborators who are more authoritative in my mind. I just happened to be the guy with the camera and the skills to compile his life and work into some kind of decipherable cinematic text. It was indeed daunting to know that my subject in this case was hyper aware of the power of the image and the mechanisms of media production.

Was there ever a point where you felt that Tony Conrad was putting one on for the camera? He’s clearly very gifted as a performer, comfortable with the camera, and aware of the power of language/image.

Was there ever a point where you felt that Tony Conrad was putting one on for the camera? He’s clearly very gifted as a performer, comfortable with the camera, and aware of the power of language/image.

He is a performer and was indeed playing for camera, but that awareness of camera also enables him to be a willing actor in his own story and he had definite opinions on what and how he wanted to be photographed. He was, however, very revealing even in his comically performative way. That’s what intrigued me. He could be “on” but also telegraphing all the thoughts and feelings required for the scene.

As Conrad says quite succinctly, “documentary filmmaking is at a completely ambiguous point right now”. It’s sometimes mixed up with trying to project a narrative that competes with Hollywood narratives. It is not always anthropological or primary source material but looking to sell tickets, streams, and downloads. How are you and Tony’s view of documentary filmmaking similar or different?

In that scene he is certainly asking that question of his students and I don’t think has a truly fixed opinion. He’s observing something we all are, that non-fiction filmmaking is expanding and contracting all over the place right now. That’s what makes it so exciting. Narratives can help sustain an emotional through line over the length of a feature film. That’s why we like them. We are storytelling animals. But I’ve always been interested in seeing how far away we can get from narrative and maximized forms that are more subconscious or free associative or even just abstract.

I think the film balances archival and vérité footage. Tell me about your process of editing the immense archives for this film and what was a breakthrough moment in structuring the film.

I think the film balances archival and vérité footage. Tell me about your process of editing the immense archives for this film and what was a breakthrough moment in structuring the film.

Nothing too sexy there. Just lots and lots of trial and error. Eventually I narrow the scope of works into those that were overtly or covertly political because they could thread together and form a bigger picture. At the root of it Tony is a political artist whose major works deal with themes of power, disempowerment, empowerment, rejection of authority or received knowledge. There are lesser known works that are outliers or just incomplete ideas and those fell by the wayside in this version of his life.

Music and sound (both on location and in post-production) is an important part of the film but it is not always easily displayed visually. Tony Conrad is well known for creating a hypnotic, almost psyhological experience, with his “Flicker” films. Did you immediately feel a challenge to take on his style, both auditory and visually, to reflect his work and character?

I wanted his works to take the foreground but found myself having to create a few visual motifs for some of the music compositions so I tried to make visuals that are more abstract and open-ended that wouldn’t take the viewer’s focus off the music but might give them some subtext for the composition. I considered just playing the music over a black screen but Tony didn’t play in complete darkness. He always supplied some visual component to the music

What is interesting about the reaction to the film? What do you have planned next?

The most surprising and heartening word I have heard the most in describing the film is “inspiring” That’s probably the one thing I was really hoping for; that a viewer would exit the film feeling invigorated and confident in their own ideas and path in life. I’m hoping to start on a memoir-based essay film about growing up in the Silicon Valley of the 1970s.

Who do you recommend Frontrunner interview next?

The painter Zak Smith

Responses