Virginie Efira on Paul Verhoeven’s ‘Benedetta’

I sat down with Belgian actress Virginie Efira in a lavish hotel bedroom in London. Intimate, a little warm, and so new that the paint was still wet when my shoulder rubbed against the beige wall. It’s not the usual small talk we begin with but much rather with Efira questioning the city’s architectural choices such as why hotel windows do not open in London the right way so that people can smoke a cigarette without alerting the fire brigade down the road. This issue is quickly resolved and the modern solution, a vape, slips out of her pocket. The discussion takes up quite a bit of our time, but when we cut to talking about director Paul Verhoeven’s new film, BENEDETTA, that’s when the conversation turns, well, juicy, unexpected, and yet true to any of Verhoeven’s work.

Efira plays none other than the film’s protagonist, Benedetta, alongside Daphne Patakia, where she’s entangled in a 17th-century taboo lesbian love affair. This is the point where it’s a bright idea to hint, as a nun, with a nun at a nunnery. A religious scandal and a hunt for sin and those who sinned ensue, and the audience will quickly realize that these pleasures were called guilty for a reason. Especially when you have an abbess such as Charlotte Rampling.

FRONTRUNNER chatted to Efira at the BFI London Film Festival and, as we are in contemporary times, talking Virgin Mary dildos, Sharon Stone’s famous interrogation scene in Basic Instinct and the extremes and violence which we can push our bodies through should not shock us evermore.

The 65th BFI London Film Festival, The Royal Festival Hall, October 16, 2021, London (United Kingdom)

Photo credit: Jeff Spicer/Getty Images for BFI

Congratulations on your performance and your new film, BENEDETTA. What an unconventional and contemporary film with a different perspective on religion and history. How did the story evolve, and who do you portray in the movie?

I am a big fan of Paul Verhoeven. I discovered his work when I was 20 years old with Basic Instinct. Then I saw all his American and Dutch films, later. I didn’t read Simone de Beauvoir when I was younger, but the female characters in Paul’s stories were incredible because he doesn’t only offer sexual territory to men. His female characters are also often struggling to survive. They are complex and don’t follow the archetypal portrayal of women. When I was in Paris, and I auditioned for Elle with Isabelle Huppert. I wasn’t hesitating for a second. I wasn’t sure if my audition would be successful, but I wanted to meet him. He cast me, and I found it interesting to see him work. Shortly after Elle, I met him at a hotel where I’m sure he didn’t recognise me, but he then told me he wrote a movie for me. I said yes before even reading the script. Now when I discovered what was in the script…first, he told me there would be plenty of sex scenes. Then, that those would be with a woman. I said, “Sure, not a problem.” Then came religion’s special place in the story, and I kept saying “no problem.” However, when Paul mentioned the book (Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy by Judith C. Brown) and how his script is based on the true story of Benedetta Carlini, I finally read it and I was amazed. Three pages in, I was convinced. It was deep, intelligent, but also hilarious. Benedetta was so sure she was alive because of God and that she would become his wife. She thought she was promised to God. In the 17th century convent, everyone had an issue with the human body and thought that it was their worst enemy. Benedetta maintained this relationship with God which got out of hand when Bartolomea, played by Daphne Patakia, arrives in the Covent. Benedetta desired her, and when her faith and pleasure intertwined, she was possessed (according to her) by a superpower. Both the film and the book question if she was a manipulator or sincere, but I think she’s both. There are other stories, such as The Portrait of a Lady on Fire, directed by Celine Sciamma, which also questions our liberty in this world and who the female body belongs to.

Would you say that Paul Verhoeven, as a director, paid particular attention to shed light on female desire, especially towards another woman?

He has been doing that before our collaboration and Benedetta. In his most well-known film, Basic Instinct, Sharon Stone is a complex character. Everybody remembers the interrogation scene where she has those stereotypical men wrapped around her finger. His camera’s point of view is with the woman instead of the men. I don’t like saying “just the woman” because she is much more complicated and layered than that. She is many definitions. It’s not only her who is desired, but she has her desires too. As I said, Paul splits the sexual territory. When I ask him about this, he says for him, there is no gaze, whatsoever. He treats men like he would women and vice-versa. As for Benedetta, in the 17th century, it was an extremely macho environment. Two women together in this era was impossible. Without a penis, what could happen?

Some people still think that these films can only be conceived because of the so-called rising power of feminists. As you said, it’s a simple story between two people who happen to be women. It doesn’t need to be complicated, and Paul is changing this perspective by bringing this nun’s story to the screen without bringing in the feminist politics.

It’s part of him. This perspective is part of his subconscious. These messages are never his aim because this is natural for him. It’s how he thinks.

I’ve read a review that said, “Finally, a film that gives Catholicism the disrespect it deserves!”. I laughed a little then I thought about it more and wondered about the truthfulness of this statement.

I will not say what I want to say to avoid being too political. I think the film respects faith because I believe faith has higher power than us. Benedetta lived with this, which gave her great strength. She found her way to God. All of Paul’s films question the capabilities of the human body. Not just the good things but everything that a person might want to hide. Paul is inspired by Flemish painters such as Pieter Bruegel, where a man urinates on the Moon. It’s a part of his cinema, and he incorporates all aspects of the human body into his stories.

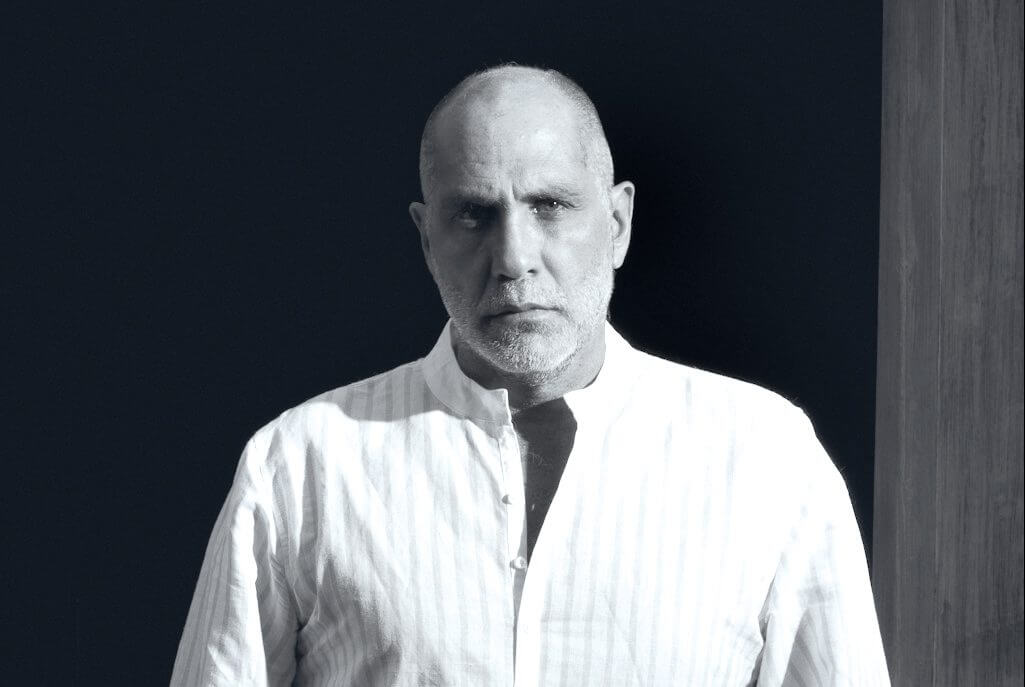

Benedetta (2021)

Dir. Paul Verhoeven

Photo credit: Pathé Films

Before watching the film, I feared that the relationship between Benedetta and Bartolomea might escalate into something like Blue is The Warmest Colour, but I’m so delighted that it does not. How did you, your fellow cast members, the director find the healthy boundaries?

When you watch a Paul Verhoeven film, you know where his gaze stands. The most important thing is trust. Every single sex scene was storyboarded. When we were building up the scene, we had to ask ourselves, “What are we trying to tell the audience?” The sex scenes are metaphors for many things such as birth, discovering the human body, which is why some moments seem exaggerated. The camera is very far, it’s observing. I can’t say much about Blue is the Warmest Colour’s director, Abdellatif Kechiche, but actors should never be told to do what they want. That should not exist. It was funny to do our sex scenes in Benedetta. There are always too many people, but Paul brings a lot of humour and lightness to set. As a woman, I like to contribute to how the scene plays out, even if I’m naked. I might be happy to do certain things, and I don’t like it when people decide what I don’t want to do on set.

These scenes should always be a conversation. That’s what turns it into a positive experience.

When you speak about Abdellatif Kechiche, what’s interesting in his film is that he always wants to offer the true-to-life look of the scene. That’s not how Paul works.

Often unexpected. So it is not a surprise when the Virgin Mary dildo enters the frame.

Yes. Some people hate it, but I love Showgirls. I thought the dolphin sex scene where she might die [was] not possible, but in Paul’s films, it is. It’s comical.

Sex and violence are recurring themes in the film, but we see it everywhere in different shapes and forms around us too. How do you think this adds to a story, and why do you feel it is important to be represented in film?

It’s a combination. The most problematic scene can also be funny. It’s about provocation. The way Bartolomea is tortured is unrealistic, but as we spoke about the importance of the body, that scene is exactly that it centres the human body. As Benedetta gains power, she doesn’t want to hear more descending voices. I can’t believe anyone who says he or she is a good character. We can never be sure of that because we are a mixture of many things. She is also a manipulator and hungry for freedom and power. She suddenly thinks she’s better than everyone else. It was difficult to play Benedetta – well, not when Paul is directing – but it’s an extraordinary character to bring to life. It was the first time I had to act as an antipathetic character, and hair and make-up were not prioritised questions. When I read the script, I also imagined a girl with a fragile body, but I am definitely not that.

Luckily, there were many other important aspects to observe in the film than women’s body sizes. I find it mind-blowing how the nuns were punished for their sins in the 17th century, yet I can only imagine that the Catholic Church was the guiltiest and most corrupt of places at that time. And even today, they got away with it: women punished by the patriarchy. Isn’t it still very relevant today?

Yes, of course, it is. For centuries, religion led patriarchal societies. I was somewhat afraid before the film’s release in France because of the public’s reaction. However, it seems that in Western societies, God is a little dead. At least in France, it is.

I find that directors sometimes hire intimacy coordinators as an easy route who do not wish to do the research and are not open for conversations and collaboration. I believe there were none on the set of Benedetta, and I’m curious to know how being in charge has benefitted and or limited your performance?

Yes, there were none. I have never worked with an intimacy coordinator; it’s often an American choice. They can be helpful, however. When you trust the director and conversations happen, it always works out. The sex scene is not the problem. The problem is when you have a director who wishes to make a sex scene to illustrate something. That’s boring. Finally, in France directors’ choices are being questioned. I also do so now, but it only happened once I was around 35 years old. It took a lot of experience and being comfortable with my identity. If you are 18 years old, it’s a very different thing. People don’t listen to you. It’s difficult to refuse to do things you are asked to do, so it can be comforting to have an intimacy coordinator on your side. However, I feel like the industry is changing. Slowly, it is changing for the better. It’s possible to find collaborators who are respectful, intelligent, and professional when it comes to intimate scenes.

Responses